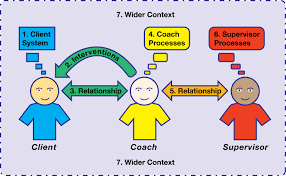

A sign of a professional coach is their active participation in coaching supervision – i.e regularly taking time out from live client work to reflect on and develop their own practice. This may take the form of a group or a one-one relationship, held face to face or virtually. For many coaches the default solution is to reach out to peers to help provide this support. This is entirely understandable given there is often a cost implication attached to using a trained and qualified supervisor. Peer supervision can be exchanged for free with someone you know and trust already and it is an opportunity to practice coaching skills. So why wouldn’t you go to peer supervision?

I would argue that while many peer supervision relationships are great, some peer supervision falls foul of dual relationships and confused boundaries. Supervision is more than ‘coaching the coach’ . The point of supervision is to work with someone who can help us to be objective about the quality of our work and hold the (potentially competing) interests and perspectives of the coach, their client and their sponsoring organisation in view. A coaching supervisor has to be able to operate as a critical partner – and that means being able to discuss the messier edges of our coaching work as well as support and celebrate our victories. If our supervisor is too much of a friend, the relationship can be in danger of a subtle collusion where we agree to support each other but not challenge enough.

In the commercial coaching world peer supervision simply doesn’t ‘cut-it’. Prospective client organisations and the big coaching houses increasingly look for coaches who have professional supervision from a qualified supervisor. Conscientious coaches also know that supervision time is essential ‘me’ time for coaches, and the knowledge of an experienced practitioner invaluable to growing their practice. So why wouldn’t you?